Sklavokambos (2023-)

The excavation on the internet

The archaeological site of Sklavokambos is located on the northern slopes of Mount Ida (Psiloritis) at an altitude of some +400m. above sea level. It is currently part of the area under the administrative responsibility of the municipality of Malevizi of Heraklion in Crete (former municipality of Tylissos), and is under the archaeological jurisdiction of the Archaeological Ephorate of Heraklion, a department of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

The site, known in the literature and partially excavated previously, began to be investigated again within the framework of a five-year research project (2023-2027). It is a training excavation of the Department of History and Archaeology (Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Crete), under the direction of Artemis Karnava.

The ancient habitation remains became known in 1930 on the occasion of the building of a carriage road between Tylissos and Anogia, a distance of some 20 km. At 6 km. to the east of the village of Gonies, and south of the road, a stone-built building dating to the 2nd mill. BCE was identified, which, in fact, forced the engineers of the time to slightly shift the original road course (fig. 1). The excavation was directed by Spyridon Marinatos, Curator of Antiquities of Crete at the time, on behalf of the Archaeological Service. Since then, no systematic archaeological research of any kind has been carried out at the site or in its immediate surroundings. The site is currently located within a fenced, expropriated area, labeled by the Archaeological Service, and is directly accessible and visible from the adjacent asphalt road.

The archaeological information we possess comes from a single, albeit detailed, article by the excavator in the Archaeologike Ephemerís, published a little less than twenty years after the excavation (in Greek: S. Marinatos, “The Minoan Megaron of Sklavokambos”, Archaeologike Ephemerís 1939-1941 (1948), 69-96, tables 1-4. The excavator identified a building with twenty (20) rooms, which he called a ‘megaron’ or ‘rural villa’, and dated it entirely to the Late Minoan I period (c. 1600-1450 BC), without any earlier building phases (fig. 2). The building appears to have been divided into two sections: North and South, which were accessed from different entrances. He assumed that the North Section consisted of the living quarters and the storerooms. The South Section, which incorporated a courtyard with three pillars, was suggested to have had been of auxiliary use and was mainly used for food preparation activities.

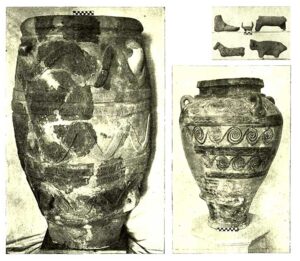

Several objects were collected during the 1930 excavation, which are currently kept in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (fig. 3). These are objects of daily use, tools and generic house equipment (handleless cups and a clay brazier, pottery of all sizes and pithoi, a stone hammer and axes, millstones and whetstones, copper plates and nails), food consumption remains (animal bones, charred seeds), cult objects (clay human foot, clay figurines, clay ox head, stone rhyton), but also luxury items, as can be seen from the elaborately decorated jug in the photograph.

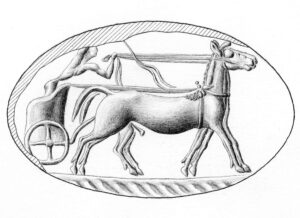

The most ‘famous’ and important find of the Sklavokambos excavation however were the 39 clay administrative sealings that were found at the entrance to the Northern Section (fig. 4). These are minute clay objects bearing one or two seal impressions, which were used to secure folded, small pieces of (animal) leather with written texts on them. The sealed leather pieces, which of course have not survived, were sent from their place of manufacture to some other location, but for an unknown purpose, and we assume that this is also the case at Sklavokambos: the leather documents and their sealings were not written or stamped on site, but they were sent from another location to Sklavokambos. Whether Sklavokambos was their final destination or not is a question that cannot be answered. The clay sealings bear seal impressions coming from many different seals of excellent quality and variety (fig. 5), which were stamped when the clay was moist.

The five-year research project of the University of Crete (2023-2027) has as its main objective the training of university students in archaeological field research methods, and the excavation season each year usually takes place between June and July. At the same time, students are invited to handle, study and integrate into the new research data material from the previous excavation, either in situ remains, or movable finds and any surviving documentation or archives, known in international bibliography as ‘legacy data’, for research purposes. An additional goal is to familiarize students with the concept of managing an archaeological site, and how it could be transformed in the future into a site for visitors through the conservation and promotion of the surviving archaeological remains as well as the production of information material for visitors.

With the cleaning and excavation research and mapping of the existing structures of the site, it is expected that the image of the uncovered building and its surroundings will be clearer. The first excavator S. Marinatos had already seen that the building was surrounded by a settlement. As far as pure archaeological questions are concerned, there is no doubt that we know little and we do not comprehend the character and importance of the building itself. The archaeological evidence that has been collected from Crete and the wider Aegean before, but especially after 1930 do not allow us to place the building’s construction or its destruction in an exact chronological frame nowadays, but, above all, we do not understand the role of this building and the settlement to which it belongs within the administrative network of Neopalatial Crete. The building appears in the bibliography as a ‘rural villa’, and it has been suggested that it served as a ‘customs office’ for passers-by (where from, and where to?). The archaeological research on Minoan ‘villas’ and ‘rural villas’, buildings of meticulous construction and rich content, which have been excavated or are being excavated throughout Crete, but especially in recent years in mountainous areas of the island, is expected to be enriched by the field work at Sklavokambos.